Disguised as a sci-fi murder mystery, “Face The Raven” is about betrayal, addiction, and the death of Clara Oswald. Possibly the best showing of the twelfth Doctor.

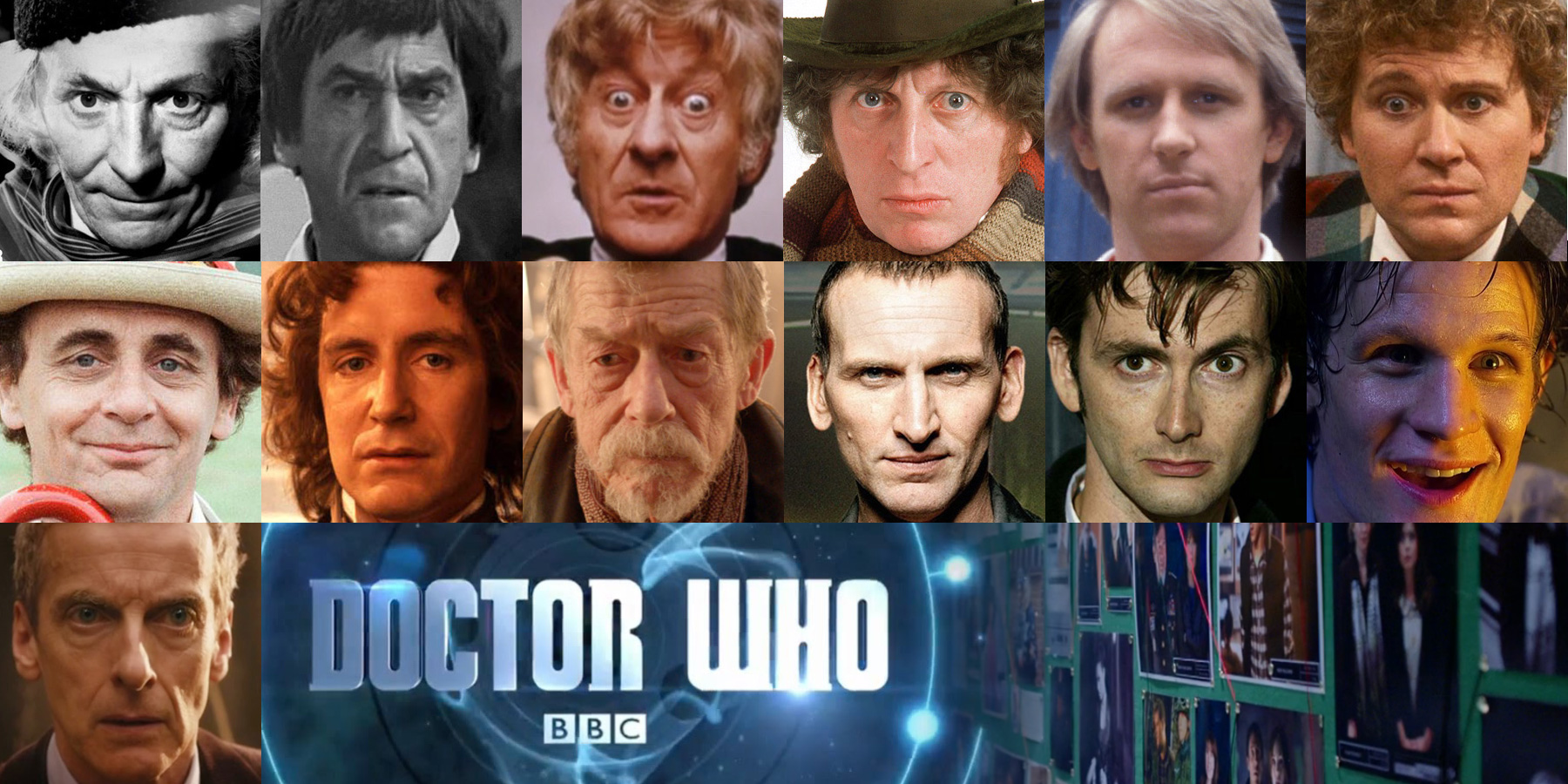

How would time with the Doctor transform an Earthly child? While endangering his companions enough to land him in court at least twice (The War Games, The Trial of a Time Lord), the Doctor somehow empowered them. Most became braver (Barbara Wright and Ian Chesterton, Rose Tyler,) smarter (Leela,) more open-minded (Liz Shaw,) more compassionate (Vislor Turlough,) or more focused (Martha Jones). Others didn’t need transforming (Sarah Jane Smith, Romana, Ace.) In spite of having their lives threatened enough to qualify for Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, most got away in good shape (perhaps there’s a support group). That’s an amazing track record.

Since not even Hank Aaron batted a thousand, other companions weren’t so lucky. Adric was killed, Donna Noble lost her memory, and Clara became a danger addict. Either she absorbed the Doctor’s worst personality traits by sheer osmosis, or her TARDIS time unlocked repressed urges (like Tegan in Kinda). Bonnie the Zygon felt pretty comfortable in Clara’s head in “Invasion of the Zygons.”

The first part of “Face the Raven” is formulaic at best: the Doctor is shown something weird, tracks down clues with new Who tech, and uses flimsy logic to find the alien refugee camp. It must be nice to write yourself out of trouble by dropping entirely new races and technology into the middle of the story. Actual whodunnits challenge us to solve the mystery before the hero does. Doctor Whodunnits are just stories to watch. The most compelling part is the second-half character journeys of Mayor Me, Clara, and the Doctor:

Mayor Me

Her Waterloo station reply is snide and vague. The original was built in 1848, the modern one in 1922.

Let’s take Me at her word, that some unnamed enemy is forcing her to give up the Doctor. Her solution is a flimsy mess, as Clara pointed out by saying “we barely got in.” Her plan is 100% reliant on the Doctor finding the refugee camp; if he didn’t, Rigsy would have died for nothing. Her plan is also overly elaborate. She should have summoned the Doctor directly, knocked him out, then slapped the teleport bracelet on him. Next season could be The Clara and Rigsy Adventures. Infinite lifespan and finite memory turned her into something far worse than the Mire she faced as Ashildr in “The Girl Who Died.” Me betrayed a friend (or at least an ally in protecting Earth). There’s no evidence that she even tried to resist. Perhaps she’s still angry about being made immortal without consent.

Please, no resistance. You’ve already lost.

Mayor Me

In this context, her apparent shock about Clara’s death is as unconvincing as everything else she’s said in this story. She showed no compassion for sicking the Quantum Shade/Raven on the old man, or presumably on anyone else in 100+ years. At best, she accepted the Raven as a public safety tax. The sudden concern for Clara is an awkward plot device to enhance Clara’s death scene.

With the exception of Clara compassion, Maisie Williams’ performance is as flat as Chuck Norris’. Her facial expression, vocal inflections and body language are exactly the same throughout the story. According to Kevin Smith and Spike Lee, directors are usually to blame when great actors look bad. Others say it’s the sole responsibility of the actor. Williams looks like like a hostage delivering her lines, hoping it’ll all work out in the end.

A better performance would have gone a long way toward understaing the refugee camp’s tense political situation; it reminds me of El Rey, the criminal village in Jim Thompson’s The Getaway. Thompson based it on his personal concept of Hell:

Doc and Carol McCoys’ half-million dollar fortune is worth relatively little with the extortionate cost of living. Their future looks bleak; nobody lives long in El Rey. Running out of money means getting banished to a village of cannibals. They’re finally inseparable, in Hell.

Casimir Harlow, reviewing “The Getaway” (1972 film) for AV Forums

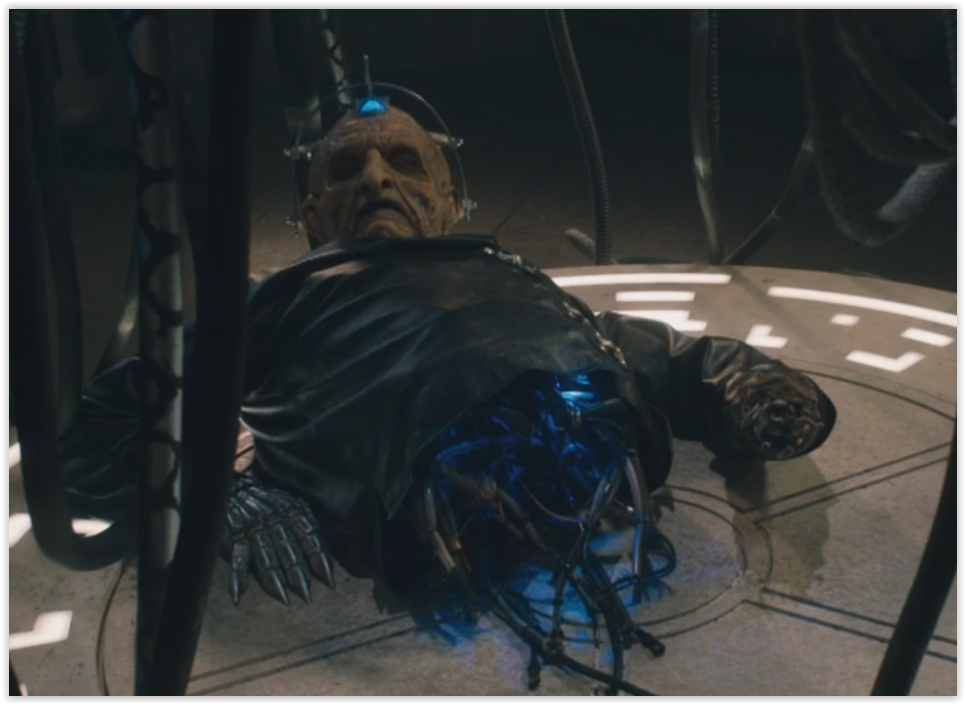

Like El Rey, Mayor Me’s refugee camp is a tense détente among many enemies. The most violent space thugs in the Whoniverse have to surpress their instincts just to survive there. This agreement is more fragile than the Zygon truce built on a pair of empty Osgood Boxes.

Clara Oswald

Clara Oswald wasn’t written very well for adults until now. From her debut in “Asylum of the Daleks” through last season’s “Kill the Moon,” she was Moffat’s second Manic Pixie Dream Girl. “I always know” from “The Day of the Doctor” was especially excruciating. She wasn’t a credible teacher.

That begins to change, starting with “Mummy on the Orient Express.” Clara seems to have written off every non-Doctor element out of her life. She’s not even bothering to hide it anymore. Even the death of her boyfriend isn’t mentioned. From Clara’s point of view, the shocked reactions from loved ones must seem silly and over protective. Those feelings, like her ordinary human life, are meaningless. She’s as cut off from these emotions as Mayor Me is from Ashildr.

This is visible in her reaction to almost falling out of the TARDIS, hundreds of feet over London. It looked physically impossible, except for two fast-motion quick shots that seem like last-minute film edits. The first shows her left foot hooked around the left door (that must’ve been hooked open like a screen door), and the second shows her right thigh pressed against the closed right door. Clara’s leg split probably couldn’t be shown in a single shot without looking like she was showing off for Jane Austin.

Clara’s plan to save Rigsy was equally reckless, but not stupid as the Doctor and Mayor Me imply. She wasn’t aware of the Quantum Shade/Rigsy contract, so how could she violate it? Since Clara’s intervention caused the Quantum Shade account to be one death short, couldn’t the balance be rolled into the next death? That could surely be worked out in a refugee camp of Cybermen, Sontorans and Daleks. The Mayor’s negotiation skills aren’t very impressive.

Why? Why shouldn’t I be so reckless? You’re reckless all the bloody time. Why can’t I be like you?

Clara Oswald

That said, Clara’s death speech is fantastic. She’s finally allowed to act like an adult. Her explanation about why she took crazy risks seems like a lazy writer hack, but successfully bridges into an acceptance of death. In an unusual moment of clarity, Clara owns up to her actions. She’s more concerned with what she leaves behind. Her lectures about Rigsy’s guilt and the Doctor’s rage are compelling and selfless. With “we’re both just going to have to be brave,” Clara might have reminded the Doctor of his bravery speech for Codal in Planet of the Daleks. Sarah Dollard‘s script gives her insight, introspection and courage I wish she’d had since her debut in “The Bells of Saint John.”

Doctor Who under Steven Moffat has (perhaps not unfairly) been accused of killing off characters for dramatic effect only to swiftly resurrect them for when the script demands a fuzzy feeling deep inside.

Jon Cooper, reviewing “Face The Raven” for The Independent

The Doctor

This episode begins with the Doctor and Clara laughing about some danger they just escaped. Since last season’s “Mummy on the Orient Express” and “Flatline,” Clara transformed from perky fanboy fantasy to action addict. In 2,000 years of renegade time travel, he’s never seen this reaction. Usually they leave. The Doctor is genuinely surprised and feels guilty, but is at a loss for how to correct this “onging problem.”

The Doctor’s guilt and helplessness reminds me a moment in The Autobiography of Malcolm X. Perhaps it’s on his reading list for understanding humans, as well as his own rebellion against the Time Lords. When recalling his criminal years as Malcolm Little, he expressed remorse about his wholesome girlfriend, Laura, becoming a herion addict. In reality, like Clara, she made her own choices.

It’s a very small universe when I’m angry with you.

The Doctor

Out of the three leads, the Doctor’s journey is the least compelling. Moffat’s Doctor is still the king of empty threats, bragging about his stats while being quite helpless. Perhaps he’s using this as a bluff, like Will Munny at the end of “Unforgiven.” But there’s nothing in the script or performance to distinguish this from similar Kirk-like bragging under Moffat’s reign. Does Moffat’s Doctor berate men this way?

In Summary

The first half of “Face The Raven” is an enertaining, but formulaic sci-fi murder mystery. Everything unique and interestsing about it is the character journeys of Mayor Me, Clara, and the Doctor. The major themes are betrayal, addiction, and the death of Clara Oswald. This is possibly the best showing of the twelfth Doctor.

TARDIS Bits

Late is better than not at all. Shut up.

- The Doctor loves scaring Rigsy.

- Nice seeing Retcon, the sleaziest drug in the Whoniverse.

- It’s always weird seeing the TARDIS fly.

- Why did Mayor Me take her scarf off so cinematically? She looked like Morris Day handing something to Jerome.

- On her way out, Clara should’ve beat the hell out of Mayor Me. It’s not like she had anything to lose. What happened to slap-happy Clara?

- I’m proud of myself for not making one Joe Flacco reference.