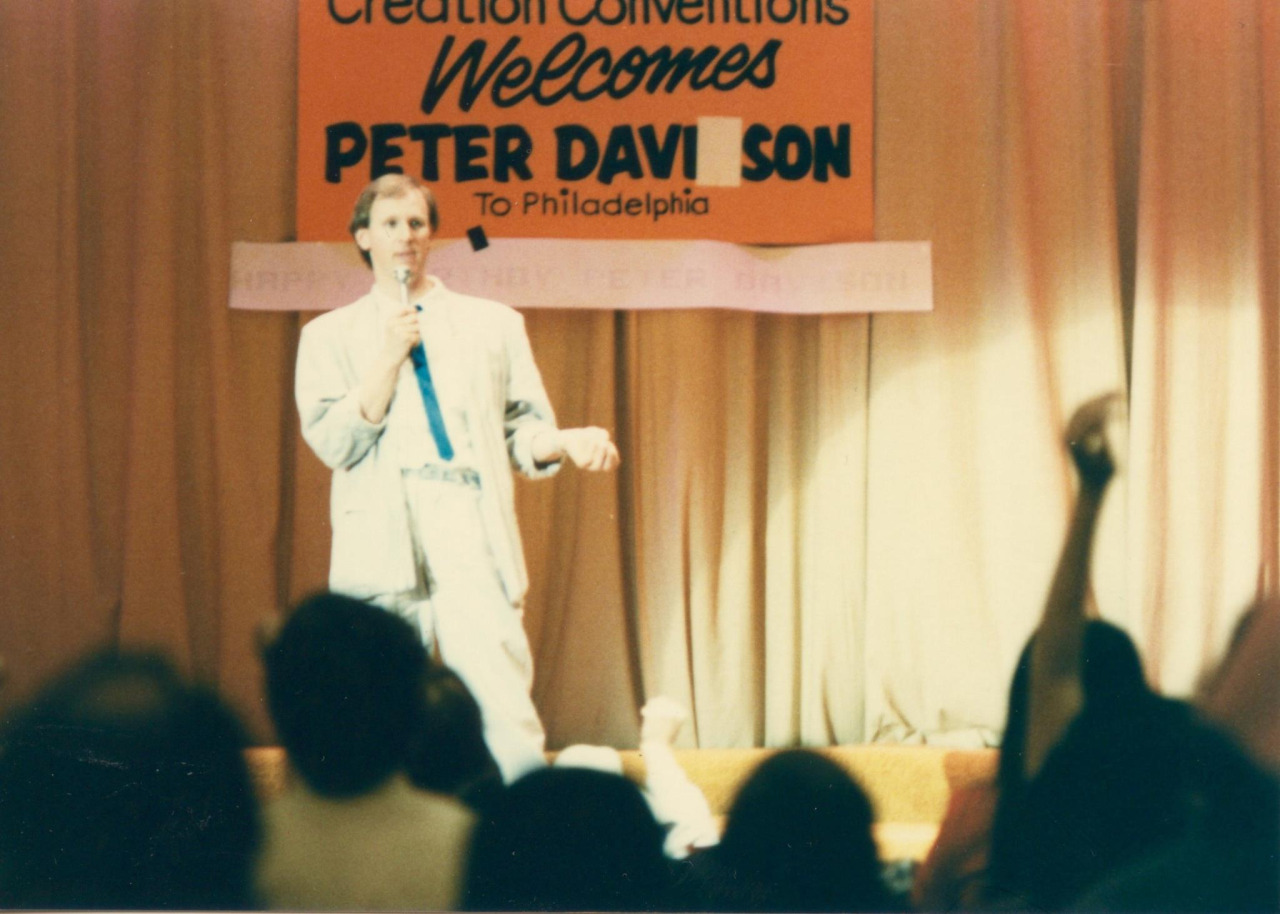

After playing the Fifth Doctor for three years, Peter Davison relinquished the celery to revive his career. Interviewed in Boston by Starlog Magazine, 1988.

The itinerary to Peter Davison’s recent United States WhoCon Tour reads more like it belongs to a rock star rather than a onetime Doctor Who. Though hardly the equivalent of a Bruce Springsteen tour, it was rigorous and exhausting for Davison just the same. However, Davison’s good looks and keen blue eyes reveal nothing — including the fact that he had just arrived in Boston, and hadn’t slept for nearly 48 hours. Davison, 35, has been acting professionally — and consistently — since he left drama school in 1972, primarily in the television medium. His track record in Britain clearly establishes him as a “hot property.” And now, with his more recent TV credits to add, establishing an equally successful career in America next should be a snap. Davison however, is quick to disagree. “I learned quite early on when I went around to see casting directors, which I did in Hollywood in 1982 after [the British series] All Creatures Great and Small was really taking off over here,” he recalls. “What I discovered was that being on a program in Britain which airs on PBS in the United States means nothing at all in terms of your employment chances over here. People are not at all impressed. The only thing they’re really impressed by is a film. If you can go to Hollywood and say, ‘I’m in this British film,’ then that’s a whole other world. But to say, ‘I’m now appearing on one of your stations, Los Angeles PBS,’ they’ll respond [in an American accent]: ‘So what?’ They may even watch it and like it, but they’ll still say, ‘So what?’ It’s true.

“This is what I was told by several people. Although they might like the program, my value over here, my being a draw because I was in Doctor Who or All Creatures — it was zilch! It was no draw at all. So, I was in no better or worse position than any other actor coming over from Britain who maybe wasn’t known at all— which was a rude awakening.”

“English actors try to be macho sometimes and pretend they’re gun-toting cops, but I don’t think we can do it,” Davison admits. That’s probably why Earthshock was the only time the Doctor used a blaster.

Although he has a tough time proving it to fans, Davison admits, “Really and truly, I’m not at all famous in America.”

Even though this is the case, it still matters to Davison that the British programs that he has been in receive American airings. “It matters a great deal,” he smiles. “I don’t know that it helps my career very much— although I did get a part in Magnum, P.I. because of All Creatures. So, yes, that did help; but had the program been successful only in Britain, it’s quite possible that I still would have gone up for the Magnum part because they came over to Britain to set up their episode. But they knew and liked All Creatures and they thought it would be nice to have me on Magnum. So, it does matter to me with that one exception…”

No More Rehearsing

Being so ensconced in “the British way” of television production, Davison experienced an uneasy transition by doing Magnum, P.I. the American way. “The one thing that really shook me was that we did not rehearse!” he announces. “In Britain, there is a definite tradition of rehearsing a part. On Magnum, we would just stand there and go through the scene once, talk through it once, and they would say: ‘OK, that’s fine, you can go sit in your caravan now.’ Our stand-ins would spend the next half-hour walking through the scene, and then they would call, ‘OK, let’s have the actors back on the set — we’re going for a take.’

“In Britain, there would have been three weeks’ rehearsal. Maybe not for that kind of program, but you would do it more than once and have a bit of a go at it. But simply to dive straight in, took a bit of getting used to. After a while, I got used to it, and you just do it. In that kind of programming, it works fine, you do it off the top of your head, it’s all very aside like. But it wouldn’t work for most of the series that we do in Britain.

“It’s a shame that American television, it seems to me, is at its lowest common denominator. We used to get programs that I thought were children’s series until I came here and found they were aired during the peak viewing hour. Things like The Dukes of Hazzard — I thought it was a children’s program. It ran in Britain during the children’s hour, but over here, it was on at 8:00 p.m. You think, ‘What? How can they be serious?’ I guess it’s partly that American audiences don’t sit down and look at the program — because if you sat down and really watched something like The Dukes of Hazzard, you would go crazy! It’s a shame, because there’s such a great possibility of doing terrific television over here. The production values are so much higher, there’s so much more available for the program, but you have this awful thing — you have to make the ratings. And Britain’s television does have that certain quality.”

The main difference between British actors and American performers, according to Davison, is the lines they can — or cannot — say. “Sometimes actors get a raw deal in America,” remarks Davison. “People say, ‘Oh, you have such wonderful actors in Britain.’ But British actors can’t say lines that American actors can say. American actors have a great ability — and I mean this as a compliment — to throw themselves into terrible dialogue with 100% conviction, which English actors cannot do. You only have to look at Dynasty to see poor people like Michael Praed [Starlong #126]. He’s a very good actor, but he had to say such awful lines, he couldn’t do it. You could see it in his face. You could see him thinking, ‘I really wish I didn’t have to say this line.’ The American actors just throw themselves into it with such zap,” he snaps his fingers. “And they get away with it.

“English actors try to be macho sometimes and pretend they’re gun-toting cops in the middle of London, but I don’t think we can do it. We look silly swaggering around trying to look as if we had American accents. Americans are great at making the action-type of program. I don’t think we have the know-how yet — in TV anyway. Our TV grew up from theater. The people who run the British TV industry were either from radio or theater, whereas in America, it’s film to television, so they know what they’re doing.

“I would love to do more work in America,” Davison continues. “I was told that I could probably make a good living over here if I [moved] and made a go for six months, and I have thought about it. Unfortunately, every time I do, someone offers me a job in Britain and I usually do that instead.” Davison’s most recent British TV series is a sitcom called A Most Peculiar Practice, in which he plays, ironically, a doctor. This show has been cited as a new BBC hit, so America may have to wait before Davison moves over for good. “If I went through a rough time in the acting business in Britain, if no one offered me anything nicer, I might well leave the country,” he says. “I don’t know that I would like to get tied up with a seven-year option — which is what you have to do if you get tied to a TV series. Although I wouldn’t like it, I would probably do it because it would be something different.”

Who Done It

The extremely likable but very shy Davison has a modest nature and self-promotion isn’t one of his strong points — but there’s no way he can deny his popularity in America or, for that matter, his appeal to the opposite sex. With a slightly reddened face, Davison rebuffs the attention. “It’s very nice. I don’t think about it as just me, but in terms of being in programs which happen to appeal to Americans. I never thought my looks were a strong point,” he laughs. “It’s a great boost to the ego, but at the same time, you have to keep your feet very firmly on the ground. You can’t convince yourself that you’re universally adored. I’m not putting it down at all — it’s very nice to come along here and have so many people interested in you — but it would also be quite easy to get carried away by it.

“For example, the people of Britain have a view, because of the media publicity, that the whole population of America had turned up in Chicago [for a convention] as adoring Doctor Who fans. They ask me all the time what it’s like to be so famous in America, and I have to say, ‘Look, really and truly, I’m not at all famous in America.’ If I get recognized in America, 99% of the time it will be for All Creatures and not Doctor Who. I don’t get recognized that much anyway — five or six times in a visit, that’s all. In Britain, it’s all the time, but not on the same scale.”

“Now that I look back on it,” says Davison of his Who stint, “I enjoyed it very much.”

Davison has completed several other British productions which are waiting to be imported into the United States. “I did a series for the BBC, which was a ‘classic’ BBC-2 serial called Anna of the Five Towns, reveals ‘Davison. “It’s based on a book by Arnold Bennett, set in 1895; it was very well received. I guess it will come over at some point — if the American market buyers like it and if people can understand the accents. Well, people will be able to understand the accents, it’s the buyers who think people can’t understand them. I did two parts of an Agatha Christie story for Mystery! and a sitcom, A Most Peculiar Practice. Then, I did a radio series.”

But what about theater? “I enjoy doing theater from time to time, but I never had a burning desire to be a theater actor,” confesses Davison. “I never thought that theater was the be-all and end-all, and television just paid the rent. I like TV as a medium and I enjoy working in it, and watching it.”

Included in Davison’s viewing is watching himself. “Yes, I always do,” he admits. “It’s the only way that you can really know what you’re doing. Many times you think you’ve done a scene well, and you see it and you realize it was really terrible. And there are times you think you’ve done a scene very badly, and you look at it and it’s actually quite good. If you draw these two lines together, what you think you’ve done and how you’re actually coming over, then you have it worked out— or maybe it’s not thinking about it too much that’s the secret. But I do watch practically everything I do.”

In the past, Davison has voiced concerns about being typecast. The actor’s presence at more Doctor Who conventions lately may indicate his fears have been allayed. “At one point, I was doing three different series which I felt I had to do in order to avoid getting typecast,” he explains. “That’s a funny word because I’m never quite sure if ‘typecasting’ means I’ll only be cast as the same sort of person, or I won’t be cast in anything at all. I suppose, when you say typecasting, what you’re really afraid of is no one offering you another job. It’s not typecasting because, in a way, typecasting is fine — within certain boundaries. Now, I play different parts but always within a certain area of work, usually light, having some element of comedy. Within that area, maybe I’m a sincere character, sometimes I’m flippant. I was a murderer once.

“I wasn’t really a mean murderer, but I was a murderer,” he says proudly. “I was just a crazy murderer. I don’t think conventions have any effect one way or the other because I appear as myself, I don’t dress up as the Doctor. But the fans are as equally interested in what I’m doing now as in Doctor Who. I think I’ve gotten clear of typecasting.”

Now that Davison is able to look at his three seasons with Doctor Who from the outside, he admits he has mixed feelings. “Looking back on the series, I don’t know. I enjoyed it very much — now that I look back on it. But when you’re doing it, it’s hard work and it’s frustrating at times, and restricting,” he says. “Money always seems to be a problem with Doctor Who. We ran out of money at the first season’s end. I was quite happy with the first and third seasons, but not really with the second. I had to make my decision to leave after the second season, and that was difficult. I had to gamble on the third season being quite good because I wanted to go out on a high note. And the good thing is that the best story I did was the last story [The Caves of Adrozani]. So, I was pleased with that. I’m sure there are many things I wish I could have done differently, given different conditions. There’s an anxious time when you leave, where you wonder if you’re going to be stuck with nothing else but Doctor Who. I don’t think I have. Since I’ve left Doctor Who, I’ve been busy doing other things, and that’s good, the security of jobs being offered.”

Having accomplished a great deal as an actor, Davison is hopeful for the chance to explore his untapped talents and become, perhaps, a writer or director. “I don’t quite know what to do. As far as my longterm future, I would love to write or direct. It’s a matter of deciding what to do. I certainly have an ambition to direct, which I think comes from having done Doctor Who. It’s something that I’ve learned quite a lot about from all my time in television, and I would like to give it a try. Should one actually say, ‘OK, that’s it. Call it a day, actor, and try directing?’ I really think that’s the only way to do it. Fortunately, whenever I get the urge, people keep offering me jobs! You have to walk the tightrope, deciding what you’re going to do,” comments Peter Davison. “I hope I’ll be directing, but I don’t know if that’s true because I don’t know if I have what it takes. I just hope that some day, I’ll get myself together enough to actually try it.”